After a snapshot of London during its transformation from

1666-1730, let’s take a look at what was happening in the United States not

long after … around the late 1700s-mid-1800s. Remember, in particular when you

look at the historical illustrations of American streets compared to London

city landscapes of a similar period, that at that time London, with a

population in 1800 of 1 million, was overwhelmingly the largest city in Europe

and one of the largest in the world. (The pictures I showed were from some of

the main avenues and spaces of London – Cheapside, The Strand and Trafalgar

Square.) New York (population 60 thousand) and Philadelphia (40 thousand) were

provincial towns by comparison.

Let’s turn to Nathan Lewis’ blog commentaries dealing

with Traditional Cities/Heroic Materialism. I strongly recommend the blog in

general, in particular his use of photographs to illustrate his arguments, his humour

and bluntness.

http://www.newworldeconomics.com/archives/tradcityarchive.html

I’ll hand the

microphone over to Lewis for a long-ish illustrated quote:

“The second Hypertrophic thing you should notice, from … Manhattan, is that

the buildings are much taller. The buildings are about fifteen stories high.

That is much taller than the Traditional City, which tends to top out around

six stories, the limits of practical use without elevators. Look at the

buildings in Siena again. They are about 4-5 stories tall. So, along with a

street that is about three times wider, we have buildings that are about three

times taller. Everything is three times bigger! That's why the Manhattan photo

and the Siena photo looked similar at first glance. The relationship between

width and height was about the same. In the case of Madison Avenue, the street

is more like five times wider, and the buildings more like five or eight times

taller.

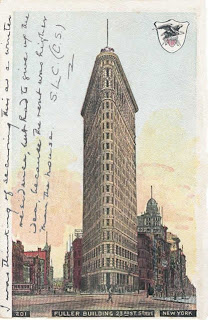

Of course, nobody started with the idea of "let's make a city, but, just for fun, let's make everything three times bigger." It didn't work like that at all. Actually, they made the Hypertrophic Streets first. Only much later did they get around to making some Really Tall Buildings to go with the Really Wide Streets. The first "skyscraper" in Manhattan was of course the Flatiron Building:

See the 3-7 story Traditional City

style buildings all around the base? Also, we can see what the streets of

Manhattan looked like in 1902, before cars.

Real empty.

See the guy walking right in the

middle of the street? He doesn't even have to wait for a traffic light (not yet

invented) because there's no traffic.

No murderous machinery in the middle

of people's living spaces. Yet.

There are some more people in the

middle of the street on the left.

The Flatiron building was completed

in 1902. It is 22 stories high.

This period image gives an idea of

what kind of impression the Flatiron Building made when it was completed.

Woo hoo! Finally, after a hundred

years, we now have some super-big buildings to go with our super-big

streets!”

Here’s another view of the Flatiron building – yes, the

traffic is indeed pretty thin.

Lewis is making a number of points about the obvious gulf between the

urban landscape/streetscape of American 19th century cities (in

particular New York and Chicago) and the “Traditional” cities of Europe. First,

the streets are much wider. Second, the decision to build urban landscapes

(both in cities and in towns) based on much wider streets emerged fairly early

on in American history – Lewis suggests the very early 1800s. Third, that at

the time the grid plans for American cities were drawn up, mobility within the

city was pedestrian or by horse (carriage or wagon), whether that city was in

Europe or America. Fourth, that from the perspective of today, the proportions

of New York streets looks “right” from a European perspective, but only because

the buildings are so large that a similar ratio to street width has been

restored. Therefore, at the time the street plans were laid out and the city

begun to expand on the grid pattern, the ratio between street width and the 3-5

story buildings that lined them would have been wildly disproportionate from a

European perspective. In essence the balance between building height and street

has been achieved retrospectively and

on a different scale, making it appear to us that in some way the urban pattern

was “designed” in anticipation of the skyscraper and automobile.

Let’s look at some more illustrations and background to

this.

Here are a couple of photos of historic Philadelphia,

which in the 1750s had overtaken

Boston as the largest city in America, as well as a link to a map of the original city centre. It seems pretty clear that – as one would expect - both the layout of the city and the form and size of buildings were, at this stage, indistinguishable from those of a port city in Holland or England at the time.

Boston as the largest city in America, as well as a link to a map of the original city centre. It seems pretty clear that – as one would expect - both the layout of the city and the form and size of buildings were, at this stage, indistinguishable from those of a port city in Holland or England at the time.

Now turning to New York, the grid pattern for which was laid

out in 1811.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commissioners%27_Plan_of_1811

Here are two views of

2nd Avenue taken looking north from 42nd Street, one from 1861 and the other

contemporary:

A road large enough for six traffic lanes now, in the 19th

century it would have been unpaved, a relative sea of mud in winter and dust in

summer. All in all, a fairly clear confirmation of Lewis’ argument. So the

question then arises: what instincts in a society of

recent immigrants which remained ethnically and culturally English, Dutch and

German could have generated this approach to the urban environment, an approach

which diverged so profoundly and suddenly from the contemporary urban formats of their

homelands?

Hi Ian,

ReplyDeleteI know this a very old blog post, but I have recently become very interested in the exact question you ask at the end. Have you found any answers since you wrote this?

Thanks!

Doug